Among the Tombstones

Like many of you who love history, I am drawn to cemeteries.

Nothing morbid or macabre, just a fascination with everything from the architectural style of the tombstones and the names of the deceased to the tantalizing clues carved in their marble markers.

One of my childhood summer jobs was mowing the Hopewell Cemetery, surrounded by cornfields and located two miles outside the small Illinois town (pop. 850) where I grew up. My father would drop me off in the morning, make sure the self-propelled, walk-behind lawn mower would start, and leave me for the day with a can of gas and the sack lunch my mother had prepared. As I mowed around the tombstones of the Johnsons, Andersons, Swansons, and Petersons who had descended from 19th century Swedish farmers and merchants, I would imagine what their lives had been like and why, so many times, they had been cut short.

A few years later I drove to Lewistown and walked the cemetery made famous by poet Edgar Lee Masters, locating many of the 212 townspeople whom he immortalized, and sometimes satirized, in my worn copy of “Spoon River Anthology” (1915). On the way home I stopped to stand beside the granite boulder in Galesburg, marking the spot where the ashes of Carl Sandburg had been scattered in 1967 after his death here in North Carolina at the age of 89.

Since then I’ve stood at dusk among the graves at Gettysburg. I’ve walked amid the somber white marble markers at Arlington. And I’ve sought out the final resting places of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and William Shakespeare. I never expected to experience some of those same emotions when last week I stopped to explore a small churchyard cemetery less than a mile from where I live.

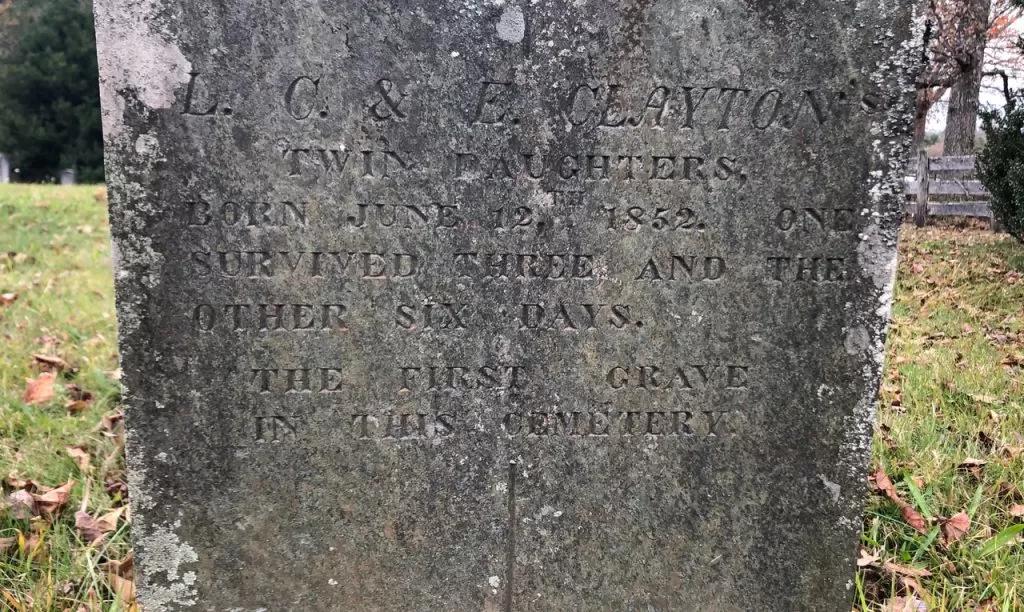

The modest white church had been built by its first members atop a cleared knoll just seven miles outside Asheville. Other than the occasional car which slowly drove along the pitted gravel road, it could again have been 1852. The community of modest, worn tombstones remain nestled close to the church. Those hardy church members were practical. No sense having to drive one of their departed a mile or two after their funeral. Or to make a separate trip in their buckboard to lay flowers at the grave of a family member or neighbor.

There are no massive monuments here. These are modest tombstones. Small, sometimes crude markers that rarely reveal any clues as to the life of each resident. No poet or playwright came forward to immortalize them.

As I walked over the peak of the knoll I found what from a distance looks like a patch of mountain stones scattered below the cemetery. Since moving to North Carolina I had heard about them, but this was the first time I had stumbled upon a slave cemetery. Words cannot describe the heartache I felt. No life can be measured by the cost or the size of a tombstone, but to think that all that marked the end of a life — of a mother, a father, a son, or daughter — would be a rock picked up out of the woods and placed upon a fresh mound of earth, seemed unimaginable, but real.

History, while fascinating, is not always something we can be proud of.

Until next week,

“Death is better than slavery.” – Harriet Ann Jacobs

Bruce